Tempus Fugit (Time Flies)

[Written in 1951, when the writer was a third former, and published in the Wellington Girls’ College Reporter.]

[Written in 1951, when the writer was a third former, and published in the Wellington Girls’ College Reporter.]

It was Saturday afternoon, the first fine one in weeks. I was riding along the main road on my bicycle towards my friend Mary’s home. She lives near Wilton’s Bush. Having arrived, I pushed open the little white gate with the front wheel of my bicycle and walked in. I laid my bicycle against the bank, then walked around the side of the house to meet Mary., in the back garden. Mary called to her mother to say that I had arrived and we were starting out. We went out the gate, crossed the road and slid down a clay bank which brought us to the Wilton Bush Reserve, on one of the main tracks.

We continued along this tr ack until we came to a tiny side path running like a brown ribbon through the bush. We crossed onto this and walked happily along listening to the birds and trying to pick the different songs. “That’s a grey warbler,” I said.

ack until we came to a tiny side path running like a brown ribbon through the bush. We crossed onto this and walked happily along listening to the birds and trying to pick the different songs. “That’s a grey warbler,” I said.

Suddenly there was a whirl of wings above our heads and looking up we saw a wood pigeon, flashing green in the sunlight. Today was our lucky day for it’s not often we see a wood pigeon.

We went on along this lovely track until we saw an old gnarled tree in front of us with a familiar cross on it. At once we broke into a run, down past the tree into the bush, for this sign on the tree showed us where to turn off to reach Mana Clearing. After a few minutes we came out of the bush into a beautiful sunlit clearing, the floor of which was carpeted with small, soft ferns and moss. After making sure that everything was the same as usual, we raced over to the other side of the clearing and pulled down out of the branches of our tree, our vine. Our vine is an enormous one. It is curved outwards at the bottom in such a way that it affords a comfortable seat.

“Bags I first turn!” I shrieked, and taking the vine pulled it to one end of the clearing and jumping onto it, I swung out over the clearing. It was lovely. For the rest of the afternoon we stayed at the clearing, tree climbing, swinging on the vine or adding to our fort which was at one end of the clearing.

Oh! Suddenly I remembered there was such a thing as time.

“Mary,” I gasped. “What’s the time?”

“Goodness, it’s ten to five. Come on! We’ll have to run,” she said.

Run! We certainly did. I had to be home at five. When we reached Mary’s place I said a hurried goodbye, grabbed my bike and pedalled off home for all I was worth.

Irene Swadling (nee Lusty)

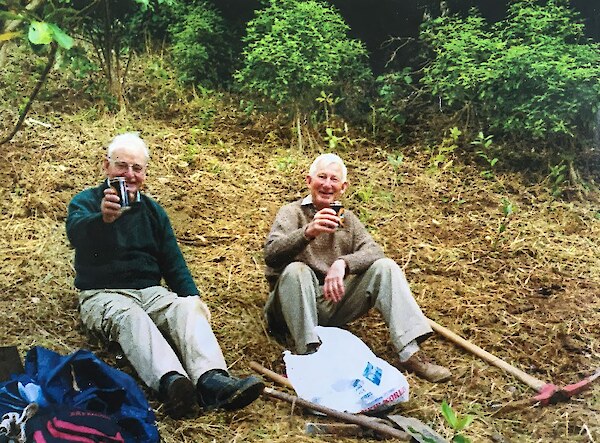

A note from Irene: Tempus Fugit is a fictional story but based on the now over 800 year old rimu tree. A friend and I discovered it although we had no idea it was at least 750 years old at that time. We would swing on the vine across the then clearing and small stream. I returned to Wellington in 1990. Diana and I were still in touch and we met up, each of us bringing two grand daughters and went in search of the tree. We discovered it was on the blue path and was 800 years old! At the time of writing the story there was a clearing but that was filled with scrubby vegetation when I returned.